Tortillería La Niña

Photos by Katie Noble

Being as far from the Rio Grande, geographically and culturally, as just about anywhere in the country, New England is not a hotbed of Mexican fare. Which is probably why when it comes to tortillas and tortilla chips, we’ve gone a bit soft. We’ve forgotten—or maybe we never truly knew—what great, Old Mexico-inspired tortillas and chips taste like.

But out of a small, nondescript warehouse building in Everett, Tortillería La Niña is doing its part to jog our memories, applying 21st century technologies to a millennia-old Aztec process to create some of the region’s most authentic tortillas. The (perhaps surprising) man behind them is Jamie Mammano, critically acclaimed chef and owner of six fine dining restaurants in Greater Boston—none of them Mexican. Mammano’s wife is from Mexico, though, and the chef became fascinated with tortillas while visiting her family south of the border, where the corn discs are expertly crafted and served three meals a day.

When the couple would return to Boston, Mammano’s wife, Monica, would complain about the perpetual tortilla drought in Boston. She refused to settle for the cheap, national-brand tortillas, to someone hailing from Mexico, the authenticity of one’s tortillas is paramount. So she’d have her mom overnight her tortillas from Mexico to Boston.

Following a behind-the-scenes tour of a Tijuana tortilla bakery with his father-in-law, Mammano approached his wife: “Why don’t we do that here?” That was in 2010, and Tortillaría La Niña was founded in 2011 with critical input from Mammano’s Mexican in-laws and family. An initial batch produced a tortilla that was too thin. Another got the thickness right, but the consistency was off. Mammano even brought in a tortilla baker from Mexico—a relative of his wife’s—to help fine tune his recipe once the business was up and running.

The recipe is broadly that of the Aztecs in Mexico and Central America, Mammano says. Many of the larger companies get bags of a corn flour mix called Maseca, which Tortillaría La Niña operations manager Brandon Child says contains preservatives and other synthetic ingredients. A friend of mine from Mexico City says discriminating diners there will avoid altogether the tortillarías that use Maseca.

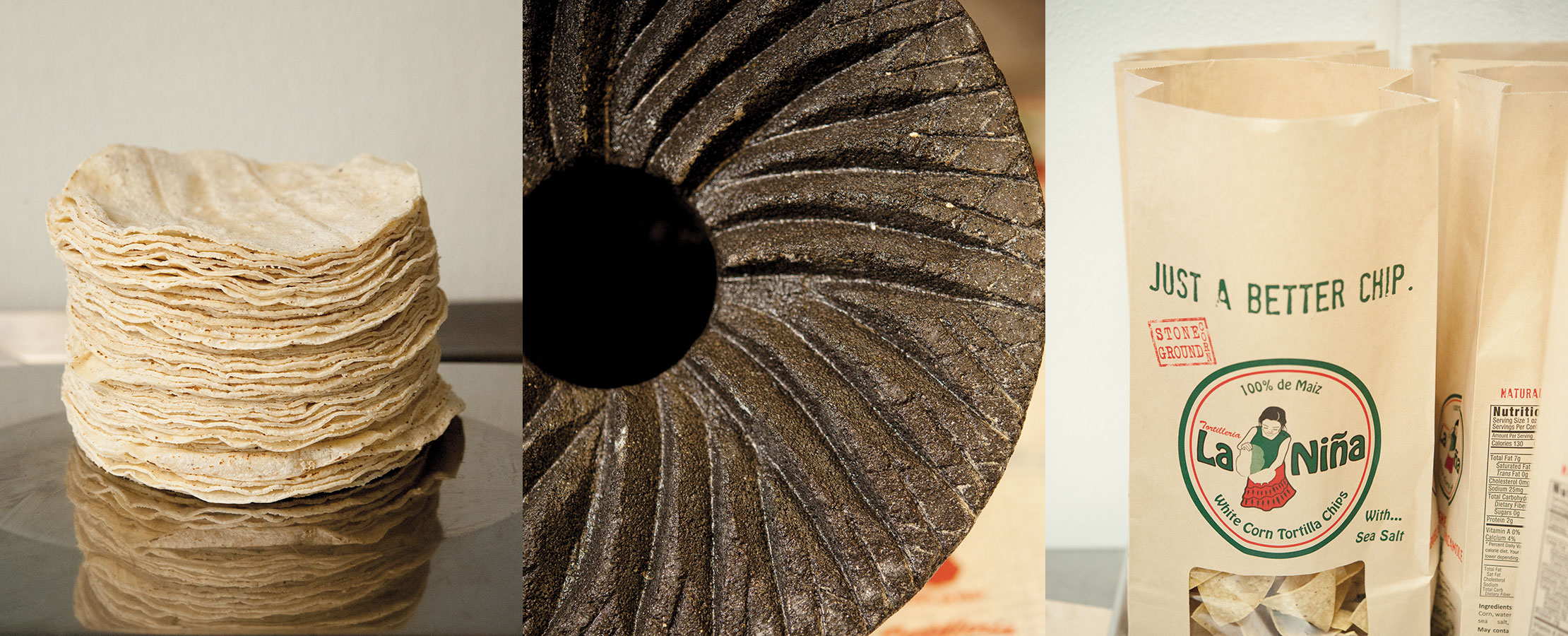

La Niña, on the other hand, receives bags of non-genetically modified corn from a small farm in Illinois. That dried corn—5,000-7,000 pounds per week—goes into two tanks where it is cooked with water and calcium hydroxide (or lime), a process called “nixtamalization” that simulates the Aztec practice of washing corn in limestone-rich riverbeds. The cooked corn is then put into a grinder, where two hand-carved stones made out of volcanic rock remove the outer husks before the remaining kernels are mashed into a corn dough called masa. The masa is then rolled out and cut into six-inch discs on a mini-conveyer and baked. The finished tortilla is stacked and packaged by hand. On the day I visited the tortillaría, workers nodded their heads to mariachi music as they carefully inspected each step of the process and closely monitored environmental changes like temperature and humidity.

“I’ve been cooking for 20-plus years of my life. I was the chef at Mistral, I’m classically French-trained,” Child says. “I’ve never made anything harder than a tortilla.”

The perfect tortilla will have just the right number of burned “puffs,” he says, a result that took thousands of pounds of tortillas and the constant feedback of Mexican and ex-pat tortilla experts (including Mammano’s mother-in-law) to perfect. Big restaurant customers like Boloco also helped Tortillería La Niña iron out the kinks and pushed them to start selling chips, which are available in more than 20 Whole Foods Markets and smaller retailers and farm stands in the area. Currently, six restaurants serve Tortillería La Niña’s tortillas, including El Pelon in Brighton and Boston, The Painted Burro in Somerville, and Taco Truck. As Boston continues to turn around its reputation as a Mexican food wasteland, that list is sure to grow.

“Very few people in the country are doing it the way that we’re doing it, because it’s hard and it’s not cost effective,” Mammano says.

For him, the corporate accounts and retail sales don’t tell him nearly as much about the quality of his product as the approval of his discriminating wife (“she won’t use any other tortilla”) and her family in Mexico.

“My mother-in-law—she eats and fries them, and I know they’re good because she’s one of the best cooks I’ve ever encountered in my life,” Mammano says. “They give it the stamp of approval.”

Tortillería La Niña 189 Elm Street, Everett 617.889.6462 laninatortilla.com