The Holdovers—Focus Features films at St. Mark’s School

DISCLAIMER: I have worked at St. Mark’s School since December 2021, and am the school librarian. There may be some spoilers here, so if you have not yet seen The Holdovers, perhaps wait to read this article until you have! It is currently in theaters and also available to rent/stream on Apple TV+ and Prime Video.

“For a life that is sound and secure,

cultivate a thorough insight into things

and discover their essence, matter, and cause;

put your whole heart into doing what is just,

and speaking what is true;

and for the rest, know the joy of life

by piling good deed on good deed

until no rift or cranny appears between them.”– Marcus Aurelius, Meditations

There’s something magical about Christmas in New England. The way crisp air smells of snow before the first flakes begin their gentle descent. The way holiday music fills hearts with glee soon after turkey trimmings have been scraped off plates and America’s Hometown Thanksgiving Parade is a distant memory. The way the energy of students’ dismissal from school for the winter break is so palpable it can be cut with a knife. The way a random act of kindness, in the form of an unlikely character courageously crossing the Rubicon, can change the life of a student in ways he will never know.

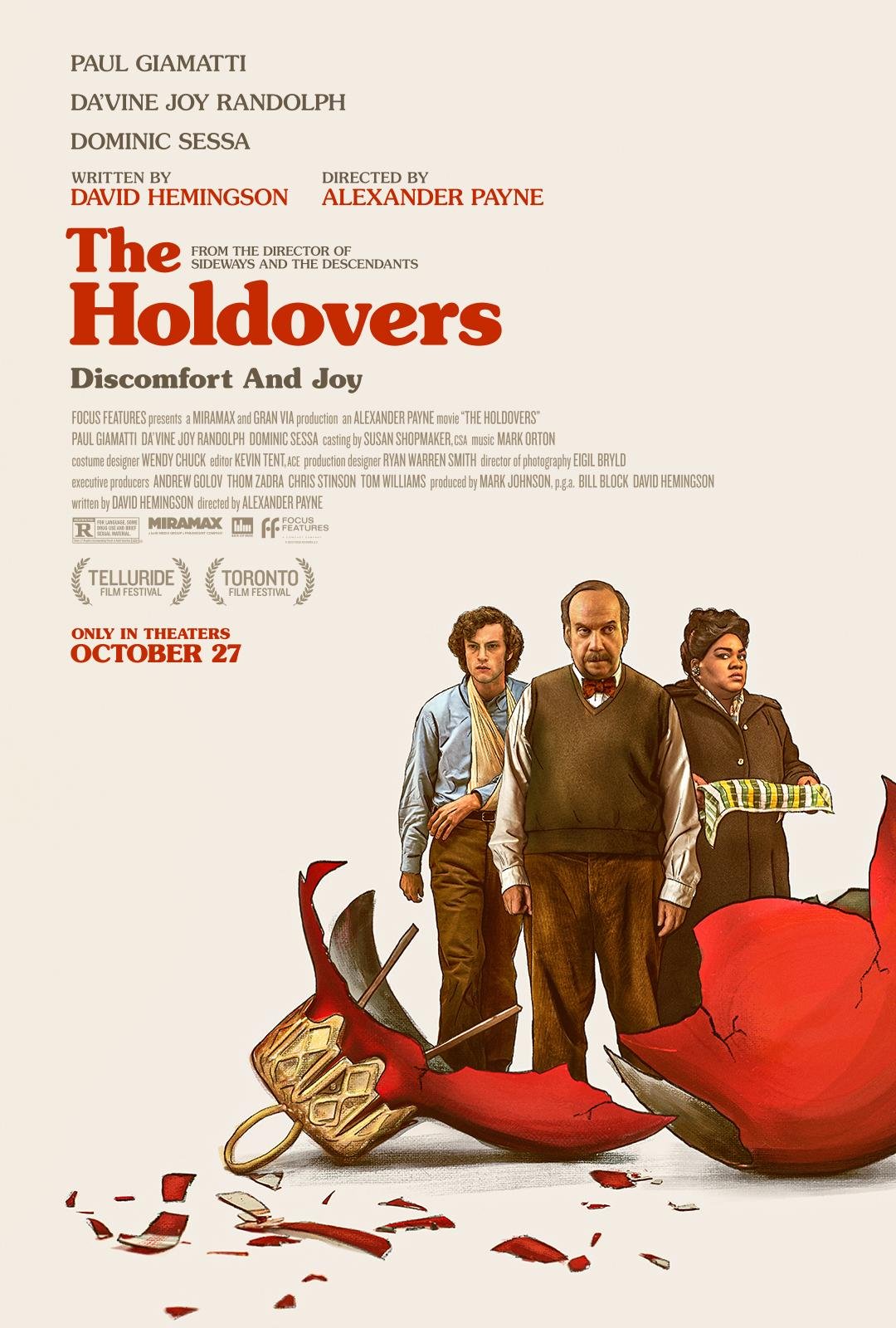

Back in March 2022, the school where I am a librarian—St. Mark’s in Southborough—was abuzz when we learned that portions of Focus Features’ blockbuster film, The Holdovers (directed by Alexander Payne, written by David Hemingson and starring Paul Giamatti, Da’Vine Joy Randolph and newcomer Dominic Sessa), would be filmed there over spring break. According to St. Mark’s director of communications and marketing Caleb Cochran, “the main locations for filming [were] the dining hall, faculty room, the hallway outside the faculty room, Elkins Gymnasium and the Trophy Room. The Main Building corridor from the front desk to the [Burgess] Center [were also] in use periodically.”

Photo: Karen B. Bento. The St. Mark’s School dining hall.

Set in December 1970 at the fictional boarding school Barton Academy, the film follows an unlikely trio of companions who are stuck “holding over” at school during the winter holiday break. Left in charge is cantankerous classics teacher Mr. Hunham, played by Paul Giamatti, who was known to rub people the wrong way: Thanks to a most unfortunate medical condition, Trimethylaminuria, he reeks of rotting fish; students don’t know where to look when they speak to him due to a particularly lazy eye; and he regularly enjoys drinking bourbon, sometimes to excess. He is socially awkward, and finds “the world to be a bitter and difficult place.” Mary Lamb, played by Da’Vine Joy Randolph, by contrast, is the kindhearted, compassionate cafeteria manager, grieving the recent loss of her son, Curtis, a Barton graduate, who “gave his life valiantly” in the line of duty while fighting in Vietnam. And then there’s Angus Tully, played by Dominic Sessa, a tall, troubled teen who likes to test his limits, and whose temptations sometimes get the best of him. There are other student stragglers at first, but after a few days they fly off in a helicopter to hit the slopes, leaving our protagonists to celebrate the holidays on an empty school campus.

Many of the most poignant moments in the movie, produced to look as though it were actually filmed in the 1970s, were filmed at other New England schools: Deerfield Academy, Fairhaven High School, Groton School and Northfield Mount Hermon, in addition to the interior scenes filmed at St. Mark’s.

According to Nick Noble, SM Class of 1976, and author of the beloved tome, The Echo of their Voices: 150 years of St. Mark’s School, the school’s founder, Joseph Burnett, “[made] his fortune as the first chemist to create a vanilla extract safe for household use, without potentially toxic levels of alcohol, and at a far more affordable cost than expensive imported European extracts made with secret proprietary formulae. Throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, bottles of Burnett’s Vanilla Extract could be found on pantry shelves in the majority of kitchens throughout much of the world.” I can’t imagine where happy holiday bakers, like Barton faculty member Miss Lydia Crane, played by Carrie Preston, would be without this achievement.

The Southborough Historical Society’s website states that in 1847, Burnett “[decided] to concentrate on flavoring extracts and subsequently [formed] the Joseph Burnett Company of Boston.” This wildly successful venture allowed him to found “St. Mark’s Private School in Southborough” in 1865, and to be a trustee of the school until 1894.

When production designer Ryan Warren Smith and director Alexander Payne first walked into St. Mark’s dining hall, they couldn’t believe their luck. With a few changes (including removing the massive, pandemic-related air filtration systems), they were able to transform it into a dining hall where bow tie-wearing, mustached teachers conversed easily sitting elbow to elbow at family style tables, and where long haired, Jefferson Airplane-loving students could pass bowls of apples, oranges and bananas to one another during meals.

“We love this room so much! It had so many existing, period appropriate bones that we knew instantly we had to shoot in it. We removed non-period appropriate furniture, and made little wooden boxes (to look like speakers) to cover non-period thermostats,” says Smith. The school was extremely helpful in removing any paintings that weren’t period appropriate. The production team kept all the taxidermy, including the prominent moose head that is mounted above the school’s portraits along the north wall. According to Noble, it may or may not have been gifted to the school when former President Theodore Roosevelt visited in the early 1900s. This version of the truth might be more legend than fact, but after all these years, it’s still up for debate.

Tables and chairs were rearranged to reflect how the seating would have been at the time, “so the teachers would be separate from the students,” says Smith. Christmas dressings, like massive wreaths bedecked with long, red ribbons, were hung on the paned windows, “and it looked beautiful,” Smith recalls. “We also had to remove the doors to the school kitchen, which is very modern, and then we shot all the kitchen interior shots somewhere else. We built swinging doors into the location that would match the kitchen location. We covered up the modern tile on the other side of the doors with faux concrete floors to also match the kitchen location. So now when [moviegoers] see the kitchen, it feels like it’s right off this dining hall,” says Smith.

In the film, Mary, the cafeteria manager, would have been responsible for overseeing thousands of meals throughout the school year. This is no small feat, and must have been frenetic at times. According to the acclaimed Boston-based food stylist Christine Tobin, “I always love working in kitchen spaces where we’re adding the last layer of set dressing to enhance the space for our actors to perform. Food on sets like this acts as an anchor and allows for actors to gravitate to a prop or action that is outlined in the script or led by the director. It is always fun to work with individuals as a coach to help with all these factors. Mary’s kitchen is typically a very busy space in the school, the set needed to feel as such and we had a great time bringing that sense of activity to life. Ha! You might even catch a glimpse of me in a kitchen scene because I was asked to be in the background as a kitchen worker!”

While researching for this article, I spent considerable time perusing the pages of Noble’s historical accounts about St. Mark’s. I learned that in the 1930s, students had to be out of bed, dressed for the day and at breakfast before 7 o’clock in the morning, six days a week. “There was formal seating, but students got their food in the kitchen, where bowls were filled with oatmeal, and occasionally plates with pancakes or scrambled eggs and a slice of ham or local sausage… Each table had a pitcher of fresh milk from Burnett’s Deerfoot Farms, a bowl of sugar, and perhaps some syrup. Large cloth napkins were set at each place, and coffee was poured into china cups from urns in the sideboard.” If this hearty breakfast had been prepared by Mary Lamb’s kitchen staff, it would have been met with her quiet nod of approval.

Being tasked with creating realistic culinary scenarios takes talent. According to Tobin, “I work closely with actors whose characters’ food presentation or engagement is to reflect who they are and where they come from. For me, the food traditions they share and the period accuracy is at the forefront of designing menus. The script is always my compass. Working with Da’Vine Joy Randolph was a delight because she gave me a real insight to what she wanted to see at her table. [Prop master] Pete Dancy and [director] Alexander Paine generously allowed me to be creative in my planning, and that is always an enjoyable way to work with food on film.” Tobin’s keen attention to detail is evident everywhere we look.

Take, for instance, the plate of festive sugar cookies Miss Lydia Crane gives to her favorite ancient civilization teacher, Mr. Hunham: bright red mittens, sky blue snowflakes, smiling gingerbread men and green Christmas trees adorned with tinsel. Her cheery lipstick-stained smile doesn’t fade when she hands Hunham this heartfelt gift, and he responds like a “troglodyte” (a term he typically reserves for his students).

Photo: Karen B. Bento. A festive Christmas tree in the St. Mark’s Sixth Form Quad, greets guests as they enter.

“Our biggest scene [in the dining hall] is at the beginning of the film, when we have all the boys eating, and then we pan down the teachers’ table and see all the teachers eating as well. This was an epic scene to set up for the props and food styling teams. Any time you are dealing with large meals like this, it’s a huge practice in continuity,” says Smith. They pulled it off without a hitch.

Tobin, who was responsible for making sure folks on the set of The Holdovers didn’t go hungry, thoroughly enjoyed feeding breakfast to 100 young men in the St. Mark’s dining hall. “Pancakes, scrambled eggs, bacon and sausage, with orange juice and milk to wash it down. The boys sure liked to eat!” Teens, now and then, have voracious appetites. I can only imagine how many dozens of eggs, whose prices had just started to soar due to supply chain issues and an avian flu outbreak during the 2022 production, had to be procured to ensure their bellies were full.

In the film, Mr. Hunham ardently believes that fresh air will do the boys good, and he makes them exercise even when “it’s like 15 degrees outside.” Despite their repeated complaints, he perseveres. Not surprisingly, physical activities during the winter months in the late 1800s were as numerous and varied as the meals served at St. Mark’s. According to Albert Emerson Benson, SM Class of 1888, the author of the History of Saint Mark’s School, “An article on training published in the Vindex gives us an idea of the ambition if not the practice of an athlete of the day. ‘Rise at five, and take a cold sponge and a rub-down. After eating an egg beaten in tea, take a five-mile run, a cold bath, and another rub-down. For breakfast, have a chop, toast, tea, little or no milk, good ale. For dinner, at one o’clock, eat meats, potatoes and greens, but no vegetables within a day or two of the race. An hour after dinner go over the course of the race. Supper should come at six, and consist of cold meats, toast or bread, and tea or ale. After supper take a gentle walk, and go to bed at ten. Don’t smoke, drink, or use coffee, and use as little salt and pepper as possible. Don’t touch pork or salt food, and have meats roasted, broiled or boiled, never anything fried. Light puddings, figs, jellies, claret and dried fruits are harmless in moderation.’ It is not difficult for men still living to appreciate that this régime was taken seriously, if not followed in all particulars.”

Based on this account, “the holdovers” didn’t have it that bad at all.

To better understand the special bond boarding school students have with their teachers, I spoke with St. Mark’s Head of School, John C. Warren, SM Class of 1974. He became head of school nearly eighteen years ago, but his love for St. Mark’s began when he first stepped foot on campus as a student. Maybe it was the school’s Latin motto, Age Quod Agis, which roughly translates to “do and be your best,” that spoke to him most profoundly. Or perhaps it was the teachers who influenced him along the way. Anyone who has stopped by Warren’s office will have noticed that his shelves are filled with framed photographs, artifacts and a diverse array of books. There is also a large bowl of candy sitting on the coffee table, and comfortable chairs just beckoning guests to sit in them. He embraces the past as ardently as he looks to the future.

When Warren was a student at St. Mark’s, his geometry teacher and football coach, Alan “Porky” Clark, was someone he would have “run through a wall for” with encouragement. “He gave me confidence in math. He understood me as a football player,” Warren fondly recalls. The beauty of boarding school is that faculty and students get to know each other in different ways. In Warren’s installation speech as head of school, he stated, “I know in my own education, the quality of my relationship with teachers has made more of a difference to my learning, and thus to my development, than anything else.” I would imagine, if a parallel universe existed where the living and the fictional could interact through time and space, that The Holdovers’ Angus Tully’s older self would have a similar sentiment.

(l-r.) Dominic Sessa stars as Angus Tully, Paul Giamatti as Paul Hunham and Da’Vine Joy Randolph as Mary Lamb in director Alexander Payne’s THE HOLDOVERS, a Focus Features release. Credit: Seacia Pavao / © 2023 FOCUS FEATURES LLC

In the film, St. Mark’s dining hall takes center stage on Christmas. If one looks closely at the three regal portraits adorning the far wall, they’ll notice (from left to right) Rev. William Greenough Thayer, headmaster (1894-1930); Joseph Burnett, the school’s founder (1820-1894); and William Edward Peck, headmaster (1882-1894), all stoically observing the scenarios that unfold under their watchful gazes. It’s in this scene that viewers begin to see a softer side of Mr. Hunham: He offers presents wrapped in brown paper bags, haphazardly tied with red ribbons, to his companions, and the expressions on Mary’s and Angus’ faces as they each unwrap used copies of one of his favorite books, Meditations by Marcus Aurelius, are particularly memorable.

Tobin notes that “the dining hall was a space that had its quieter moments. An intimate meal, in an overwhelmingly large space, always lends an emotional or dramatic feel.” This is especially true of the Christmas dinner that Mary selflessly prepares. “She used what she would have found in the freezer and pantry in her kitchen because deliveries were not being sent due to the holiday break. It was composed of brown sugar-glazed spiral ham with ham gravy, cornbread stuffing, creamed spinach, glazed carrots and soda biscuits with butter,” says Tobin.

There was also a traditional apple pie for dessert. Whether it was made using thickly sliced Golden Delicious or Granny Smith apples, it no doubt sweetened the evening. Not only was the dining hall transformed, with addition of the sparsely decorated, “Charlie Brown”-style tabletop Christmas tree that Hunham had picked out from Red’s Trees that morning, but an open bottle of Old Forester bourbon sat casually between adults as they chatted amicably. It is Angus’ heartfelt compliment that completes the meal though, when he states, “I don’t think I’ve ever had a family Christmas like this before. Thank you, Mary.”

On movie sets, creating verisimilitude can be challenging. This wasn’t the case in The Holdovers. “These intimate moments feel so warm and real, partly because of the talented actors, but I must admit I feel the warm tones of the wood walls and the history they contain help with making the moments feel real and inviting,” says Smith “We loved shooting at St. Mark’s so much. The location was incredible, and the people we dealt with went above and beyond to help us make the best film we could. We will be forever grateful for all that St. Mark’s contributed to the film.”

At the very beginning of the film, Mr. Hunham is called into Barton Academy’s headmaster’s office. When he spies a bottle of Rémy Martin Louis XIII cognac on Dr. Hardy Woodrup’s desk, he is nonplussed. Dr. Woodrup’s main concern is that as teacher in charge, Hunham ensures “the boys’ absolute safety and good condition.” What we learn by the end of the story, is that Hunham not only ensures the boys’ safety, but that he is the only one to cross the Rubicon.

Resources: Benson, A. E. (1925). History of Saint Mark’s School. Privately Printed for the Alumni Association.

Noble, R. E. (2015). The echo of their voices: 150 years of St. Mark’s school. Hollis Publishing.

Warren, J. C. (2020). Reflections on St. Mark’s School. Printed in the United States of America.

BOARDING SCHOOL BOURBON BALLS by Karen B. Bento

Photo and styling by Karen B. Bento

It is no secret that The Holdovers’ cantankerous classics teacher, Mr. Hunham, enjoys his Old Forester bourbon. In homage to this predilection, I created a recipe for bourbon balls.

When the story opens, Barton Academy is closing for winter break, which means any food that Mary Lamb, the kindhearted cafeteria manager, prepares for “the holdovers” would have to be found in the pantry—no deliveries would come until January. Walnuts were present in various scenes of the film, so I used them instead of pecans. I included vanilla extract as a nod to St. Mark’s School’s founder, Joseph Burnett, who was the first to produce it commercially for the masses. It also adds an extra layer of flavor to what I hope will become one of your new Christmas treats. And the Old Forester was the Christmas dinner drink of choice for the grownups in the film. Sorry, Angus Tully!

NOTE: Before beginning, use a food processor to crush the vanilla wafers into fine crumbs. Alternatively, you can place them in a sturdy plastic bag and crush them with a rolling pin. Use the food processor to finely chop the walnuts. Set both aside.

Makes 3 dozen cookies

1½–1¾ cups vanilla wafer crumbs (one 11–ounce box of vanilla wafers)

1¼ cups finely chopped walnuts

1 cup granulated sugar

½ cup Old Forester bourbon (or bourbon of your choice)

1¼ teaspoons pure vanilla extract

¼ cup granulated sugar for rolling

In a large bowl, use a whisk to combine vanilla wafers, walnuts and sugar. Pour bourbon and vanilla extract into the dry ingredients. Thoroughly mix until well incorporated. Dough will be moist and somewhat crumbly. This is normal. Cover the bowl with plastic wrap and refrigerate for 1 hour. This will make the dough easier to handle.

Once chilled, shape dough into one inch balls. Place on parchment paper lined baking sheets.

Pour sugar into a small, shallow bowl. Roll each ball in sugar until generously coated, and return to baking sheets. Refrigerate for at least 30 minutes, to set, before serving.

To store, refrigerate balls in a lidded container, for up to two weeks. Place parchment paper between layers so bourbon balls don’t stick together. To store longer, freeze them in an airtight, lidded container for up to three months. Allow them to come to room temperature before serving.

Optional: Pour yourself (or your guests) Old Forester neat in a rocks glass.

This story and recipe appeared as an online exclusive in December 2023.