Increased Mussel Mass? The Uphill Battle for Offshore Mussel Farming

Photos by Adam DeTour and Aram Boghosian

Here in Massachusetts we love our bivalves—our crispy North Shore clam rolls, our briny Cape oysters, our succulent day boat scallops—and we love our mussels, too, but we don’t produce them here. Why not?

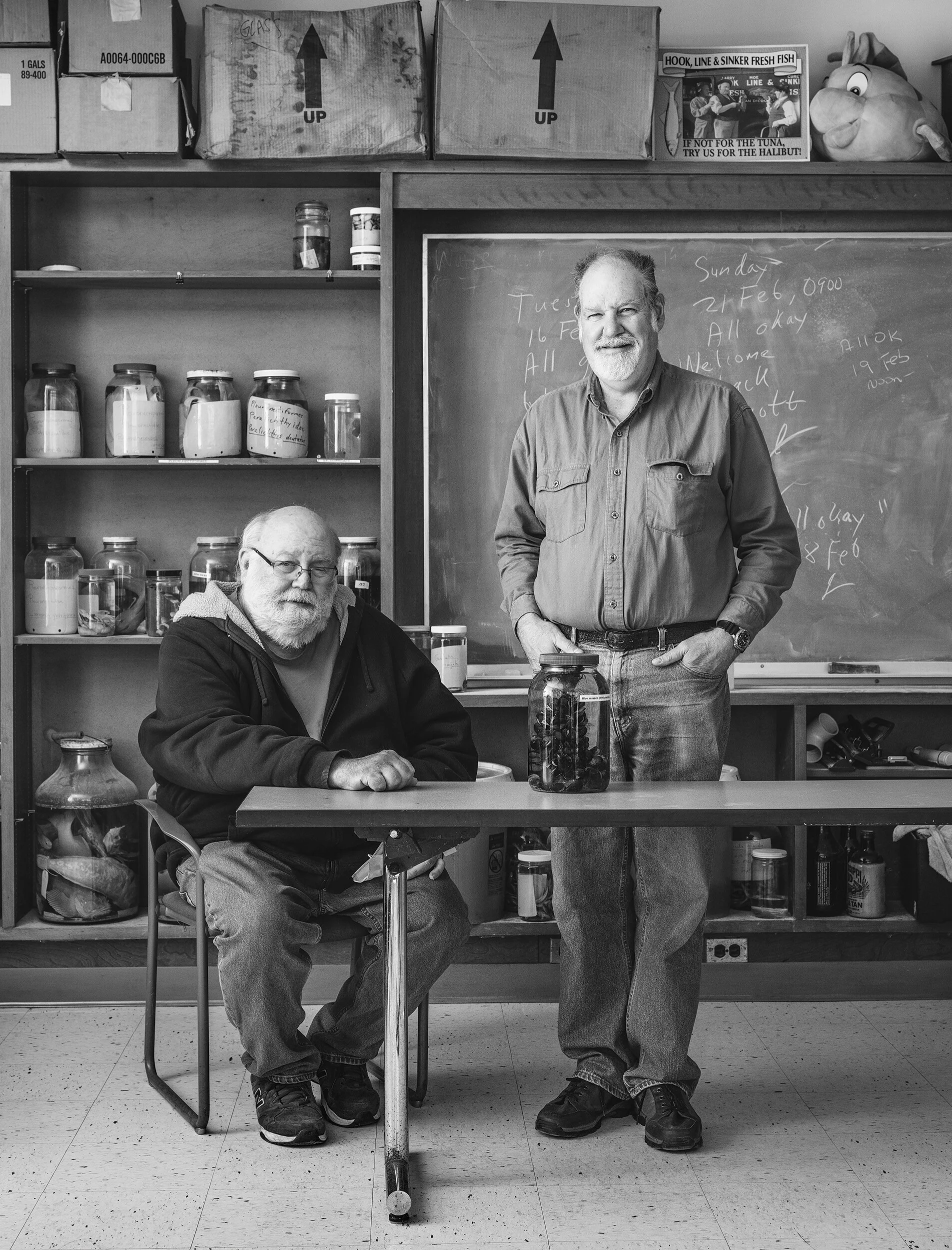

Despite a growing demand for local mussels, 85% of ours are imported, mostly from Canada—225 times the amount we produce. At Salem State University’s Cat Cove Marine Laboratory, marine ecologists Mark Fregeau and Ted Maney have worked for eight years on an aquaculture project that could deliver a fresh product for hungry consumers and an added revenue stream for the local fishing industry. In federal waters seven miles off Cape Ann, the pair are piloting the first offshore mussel farm on the East Coast. Their findings are exciting—but in February, the university announced that the lab would be shuttered.

On Cat Cove, just beyond the power plant on the outer stretch of Salem Harbor, a squat brick bunker-like structure is tucked into the slope by Smith Pool, a dammed-off edge of the harbor. In one room, five-foot plastic columns half-filled with gurgling emerald green and sepia liquids, algae to feed the bivalves, glow. Another room houses rows of mostly empty plastic tanks connected by PVC pipes where, in season, shellfish spawn, form into larvae and settle before being switched from filtered water in the lab to natural water in the pond. The place feels abandoned; just three students are currently engaged in research there.

“The significant cost of this space was not sustainable,” says Corey Cronin, assistant vice president of marketing and creative services at Salem State, in a statement, “as the university faces pressing needs to add faculty in a number of high-demand academic areas and focus its resources toward student success initiatives.”

The offshore farm began to take shape eight years ago, but Fregeau and Maney started exploring coastal mussel farming a decade earlier. Trained as scientists, not farmers, they mastered the specialized gear required for an aquaculture farm. When the opportunity to move offshore with help from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) arose, they abandoned the coastal work and turned to the open sea.

In state waters close to land, there was too much activity and competition for resources: lobster fishery, fishing, recreational boating. They needed a minimum of 30 acres of open ocean for a viable commercial endeavor. Anticipating pushback from the fishing community, they asked their captain Bill Lee, a former commercial fisherman and captain of the Ocean Reporter (a 44-foot fishing boat out of Rockport that transports the pair from lab to farm), to find areas that weren’t being fished—in federal waters at least three miles out, but mindful of fuel costs to the fishermen and -women they hoped would one day work the farm. In 2016, a year when wild blue mussels were nearing extinction, the lab deployed their first three long lines off Cape Ann, an hour’s trip from shore. In September 2017, they harvested their first 150 pounds of mussels.

The farm looks like nothing from the surface, a few buoys bobbing on the water in the middle of the ocean. Fifty feet below, a 400-foot line suspended between vertical poles “like a giant clothesline” is rigged with a series of fuzzy vertical ropes where the mussels settle and grow, anchored to the ocean floor by two 1,500-pound anchors. The site is permitted for three lines now; at full capacity with 20 lines, it could produce 15 to 20 thousand pounds of mussels per longline annually.

“Oh, they’re delicious,” says Maney. “A little sweet. They’re cleaner. I think they’re getting a much better supply of food offshore. I mean, there’s a reason that the Gulf of Maine is, or was, the world’s largest and most productive fishing bank.” Roger Berkowitz, then CEO of Legal Sea Foods, loved the product and helped to fund the project. “Roger would’ve loved to have his own mussel … this is my mussel. He could even market it that way. Just like the oysters: Every oyster farm markets their oysters as theirs and they’re better than everybody else’s. So, that’s what you can do with a farm.”

The Atlantic Blue Mussel is native to the North Atlantic and, like lobster, it was long considered a last-resort food, used mostly for bait by the Wampanoag and plucked handily from the rocky shore by desperate colonists. For centuries they were largely ignored in favor of clams and oysters.

“I think a lot of the early mussel harvesting that was done was a very localized thing; just the communities where they were being harvested would consume them, for the most part,” says Fregeau. “Oysters have been around as an industry for at least a century or so.” A raw product especially vulnerable to toxins, oyster farming is strictly regulated but the restrictions are well established and understood. In Canada, where most of our mussels come from, the industry is heavily subsidized and also coastal—there are no offshore farms to speak of. A new industry on the open ocean, beyond the borders of the state, the Cat Cove project is caught between state, local and federal regulatory bodies, accountable to a staggering array of agencies and governances. If the project were to scale and the mussels became commercially available, they’d be considered an import and permitted as such.

The deep water confers many advantages. Water temperature and food supply, the most important factors for a healthy crop, are more consistent away from the shore, where the plankton “grows like crazy” in winter. When the water temperature drops in coastal waters, food sources disappear and the mussels’ development pauses, but offshore they’re fed year-round and grow faster. Warmer waters that cause a midsummer die-off on the coast are less threatening to an offshore operation. The water depth offshore also protects from another major challenge to coastal operations: Eider ducks eat mussels whole and are able to dive up to 30 feet—these long lines are just a bit too deep for them to reach.

Many of the challenges facing the offshore farm—warming waters, regulatory uncertainty—are endemic to the seafood industry. The risk of harmful algal blooms is the same on the coast as offshore. Mistrust from the fishing industry, often generations deep, has been a hurdle, but before the pandemic the team felt they were making inroads with that community. Maney and Fregeau agree that the biggest hindrance to the offshore farm is right whales. Endangered since 1970 and in the midst of an Unusual Mortality Event since 2017, the North Atlantic right whale is one of the world’s most endangered large whale species. With fewer than 400 individuals remaining, just one death could have profound implications. Entanglements in fishing gear and vessel strikes cause a majority of deaths, mostly in Canada. NOAA’s concern for whales has slowed the addition of more long mussel lines, but Maney is entirely convinced that their concerns, based on data gathered from “fishing here, lobster traps, crab traps and gill nets,” is not relevant to the offshore farm, where the lines are anchored and would break under tension should a whale pass through.

L to R: Mark Fregeau and Ted Maney

Maney and Fregeau were caught off guard by the closure announcement, and the future of the lab and the farm are uncertain. The site belongs to the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries, with whom the university has a memorandum of understanding. “If Salem State doesn’t want to have anything to do with the farm, or is not willing to support it beyond August, then we’re hoping they’ll allow us to transfer it, and we can transfer it to anybody.”

Though Roger Berkowitz is no longer at Legal Sea Foods requesting 7,000 pounds of his own branded mussels each week, the market for local mussels continues to grow and a new champion may be waiting in the wings. SeaAhead, a bluetech startup platform founded in Boston, has shown interest in using the farm to test projects like hydrophone video to look and listen for protected species, especially whales. Their Blue Angels Investment Group works with “the blue economy, rebuilding the working waterfronts and technology development for things like aquaculture.” There is hope, but things will need to move quickly. Permit conditions require a trip to the site every two weeks. If a new funding source isn’t found by August, the farm will need to be dismantled. “I’m not giving up, and Mark’s not giving up,” says Maney. “Salem State might give up, but we’re not.”

This story appeared in the Spring 2021 issue.