Durgin-Park Employees Reminisce After Closing

On Jan. 12, 2019, Durgin-Park, the restaurant where your grandfather dined—and perhaps your great grandfather before him—served its last meal. When an iconic Boston institution that’s been part of Faneuil Hall for over 192 years, and as its own sign says was “Established Before You Were Born,” closes its doors for good, precious memories can become things of the past.

Tourists, executives and families will be hard-pressed to find anything like Durgin-Park any time soon. It’s been serving the same classic Yankee fare that merchants, fishermen and longshoremen enjoyed in 1827 when it opened for business. Sure, surly waitresses slung tongue-in-cheek insults across the wide expanse of the dining room, but those interactions only added to this landmark’s charm.

On a bitter cold day soon after its closing, I caught up with some of Durgin-Park’s staff as they busied themselves deconstructing what has been part of many of their lives for decades. These conversations are meant to preserve some of what is most dear to them.

Gina Schertzer, a petite, straight talking, head waitress has been an essential part of Durgin-Park for the past 43 years. Not only does she dish out sass, but wisdom that only comes with age. That, and lots of great stories. Although the restaurant’s immediate future is uncertain, Schertzer told a disappointed tourist—who had traveled from Springfield with his aunt in hopes of celebrating her birthday—to “Keep your fingers crossed and say a prayer. It’s not over till the fat lady sings.”

In 1976, Schertzer made Durgin-Park history as its first female bartender. She didn’t let any tensions that existed in the seventies deter her. “I was taller, I was 44 years younger, I had dark hair and a body that wouldn’t quit,” Schertzer shares with a hearty laugh. “They loved me. The bar was four-deep, and we had a teeny, tiny window over there, and I would see some of my customers come in and I’d have their drinks ready for them on the table. We had the FBI on one end, the lawyers, we had the marketmen over here and the wise guys down here.” There’s a glint in her eye as she remembers the good ol’ days.

Gina Schertzer, head waitress, and Roberto Reyes, executive chef, give each other a quick embrace. Reyes, who was working alongside staff to dismantle the kitchen, stopped what he was doing just long enough to joke about who makes the best meatballs. Photo: Karen Bento

When Schertzer sees executive chef, Roberto Reyes, walking past, she gives him a big hug. They’ve worked together for decades and share a very special relationship. “He’s gorgeous. Thank God I’m not 50 years younger, I’d be chasing him down the stairs!” jokes Schertzer. He prepares her special meals sometimes. “I come from the Dominican Republic, and when you sacrifice the life of an animal, nothing goes to waste” said Reyes. When he asked Schertzer, since she’s an old school Italian, if she’s ever eaten tripe soup before, she told him, “Oh my God, my mother used to love it!” So Reyes made it for her even though it’s not on the menu. It brought him such joy to do this for her. “It was delicious. I love him. And I’m giving him my grandmother’s pasta fagioli recipe,” said Schertzer.

She croons about what a fabulous job Reyes does in the kitchen. “Everything is made from scratch. There is nothing back door. The Yankee pot roast is neck-in-neck to the prime rib—slow cooked beef brisket simmered for hours and the ingredients he uses—you can’t imagine. The broth that it is cooked in, is the best tasting beef broth you’ve ever had in your life with the seasoning! Rene Olivia is tops in the kitchen too. He’s a tremendous guy. He loves this restaurant, and has been here over 30 years.”

Schertzer isn’t the only one to dish out a healthy serving of sass. Waitress and shift leader, Judy Almonti, has worked at Durgin-Park for 40 years. “We’re considered the Witches of Mid Hall—Gina & Judy!” said Almonti while stifling a laugh. When asked if they had ever gotten into any trouble while working together, they had each other in stitches. “Never in trouble, not one day in here! I was fired every other day for the first 12 years, but I came to work the next day anyway,” Almonti recalls as she tries to maintain an innocent face.

And there are others. A tall woman with jet black hair, Laura Seluta, has worked as a waitress at Durgin-Park her whole life. For 30 years she fell in love with management, coworkers, and people she met along the way. The restaurant’s closing has been very hard on her. “I’m devastated. I’m heartbroken for the people that have such fond memories of this restaurant. The stories people told me in the past week about how much this restaurant has meant to them just makes me cry,” said Seluta. “Everyone has been so nice and caring, hugging me and kissing me, like I was family. The way they were treating me was amazing, I could cry right now.” She’s hoping someone will buy it. “That’s my dream and everyone that’s worked here a long time—it’s their dream too.”

Amid the scratching of wooden chairs dragged across the tile floor and the clanging of silverware dumped into trays by fellow coworkers, Seluta helped lead server and best friend, Frank Cirigliano, stack glass racks behind the bar. She recounted having “seen it all,” while working the floor. “I could write a book that would be as long as your arm, said Seluta.

Cirigliano was taking good natured jibes from the crew in stride. Schertzer yelled, “I love him like a son. Take a picture of his legs—he wears shorts all the time!” He responded with a sheepish grin, “I usually don’t give in until it’s cold.”

Laura Seluta, 30 year veteran waitress, helps Frank Cirigliano, shift leader, stack glasses, box up bottles of liquor, and clear off the long wooden bar in Durgin-Park’s Gas Light Pub. Photo: Karen Bento

To some, Durgin-Park will always be more than just a place where “history is served.” In the 1970s, Elizabeth Motta’s mother worked here. Then, in 2008 when Motta turned 16, she started working downstairs in the Gas Light Pub as a host, server and bartender. For the past two years she’s worked in management handling the restaurant’s social media accounts, event planning and advertising. “I’ve done a whole smattering of things.”

Motta thoughtfully recalled how much Durgin-Park has meant to her. “[It’s] such a special place, not because of the history, which is very special, or because of what we serve—it is most definitely the people that work here. It’s such a mixture of races and ages and people in various socio-economic stages of life, that somehow we all come together and make a really beautiful, dysfunctional family.”

When Motta went to Suffolk University, she continued working at Durgin-Park. To her, home was not in her small dorm room, but here, “because this is where my family is. This is where my people are.” During her freshman year, when she was nervous about everything, Motta found solace in the sage advice of her elders. She’d sit down with them, at the red and white checkered communal tables, and they’d say, “Well, you know, ya gotta keep going. Ya don’t want to end up like us—we’re lifers.” But she “wanted to be a lifer—but maybe not a lifer server. So they were definitely very instrumental in my whole life throughout growing up.”

Staff pose in front of the iconic Durgin Park Market Dining Rooms sign for what may be one of their last group photos. From left to right (back row): Felix Hernandez, Frank Cirigliano, Anthony Lenox, Gina Schertzer, Laura Seluta, Martial Merino and Chris Perez. From left to right (front row): Allison Dunbar, Judy Almonti, Barbara Muir and Ladley Rosa. Photo: Karen Bento

When news of Durgin-Park’s impending closure made headlines, tourists started coming back in droves. “Over the past week, people have come in that haven’t been here in years. They’d tell me, ‘I drove from the Cape, I drove from Connecticut, I drove from New York.’ And everyone has a story, everyone has a memory, everyone has something. So I think to myself, what kind of a restaurant has that? It’s such a unique concept to have in a restaurant that I don’t know how they could ever duplicate this place. I’m just praying that someone comes in to open it—to do it again. It’s too special to let go,” said Motta.

Motta’s sentiment is echoed by Schertzer. When her friend, Martin Kelley, bought Durgin-Park in the 1970s from James Hallett, he brought her with him. Her deep attachment to this restaurant is obvious. “You have feelings for the coworkers that you work with—it becomes a family—it’s like a binky to us. Whenever we have problems at home, or we have things on our minds, whatever it is, we all come here to re-energize and count on one another. So it’s a wonderful, wonderful place, a great family.”

It’s not just the camaraderie that compelled Schertzer to stay, it’s also the people who touched her heart. “I have one customer that I had for so many years, he’s passed now, but his name was Carl Barron. His father started bringing him in here when he was four years old and he was 97 years old when he passed. This was his favorite restaurant and he brought people in from all over the world.”

He was a good man. “He was the type of man that if he made it in life, he gave it back.” After 9/11, Barron wanted to help make a difference, so “he brought the police commissioner, the fire commissioner, the FBI, the bomb squad—he would bring people in—and for weeks after 9/11, he would send them over to Israel to see how security was done and how they operated in Tel Aviv. Every single year he did that since 9/11. He made such a tremendous impression on everybody,” noted Schertzer. “So after he did that, he’d bring 75–100 people into the restaurant, and he’d do this maybe six or seven times a year. He always gave back to society.”

Schertzer reminisces about her good friend and past manager, Michael Ferris too. “He worked here for about 30 years and was very dedicated. He loved this place. He is a wonderful, wonderful man.” A smile spreads across her face as she recalls his kind gestures. “He would book the Peter Faneuil Room for all of us, and he would say to his employees—even to the stockmen—‘I wouldn’t be as successful as I am without you. You count, you matter.’ It was so touching that the lowest employee—he’d put them on a pedestal as if they were the vice president. He impressed me just about as much as anybody ever could impress me.”

The recipes for Durgin-Park’s New England comfort foods haven’t changed much in the past two centuries: steaming bowls of clam chowder; fresh Boston schrod covered in breadcrumbs; Yankee pot roast smothered in brown gravy; enormous cuts of juicy, prime rib; baked Indian pudding topped with vanilla ice cream; jiggly cubes of coffee jello topped with whipped cream. And the restaurant’s specialty: Boston baked beans—always made with navy beans—and slowly baked in traditional brown, glazed crocks.

Durgin-Park’s Faneuil Hall entrance. Photo: Karen Bento

And so it goes. Eventually, the sun begins to slant across framed sepia photographs, faded newspaper articles and memorabilia of bygone eras. When the wind kicks up, the bright red, white and black Durgin-Park flag hanging outside wraps itself tighter around its pole. Braving frigid temperatures, tourists walk past the restaurant’s Faneuil Hall entrance. Perhaps they are thinking about the oyster stew and piping hot bowls of clam chowder, made with freshly caught seafood and delivered daily, that have been on the menu for nearly 200 years. Staff still bustle in the kitchen, scrubbing pots and pans, wiping down stainless steel countertops and packing up miscellaneous objects. The Christmas tree is shoved back into its box as a few sparkly, gold and red ornaments roll onto the floor. Saturday night’s whiteboard, with the words ‘lobster bisque’ still scribbled in blue marker, gets tossed in the garbage.

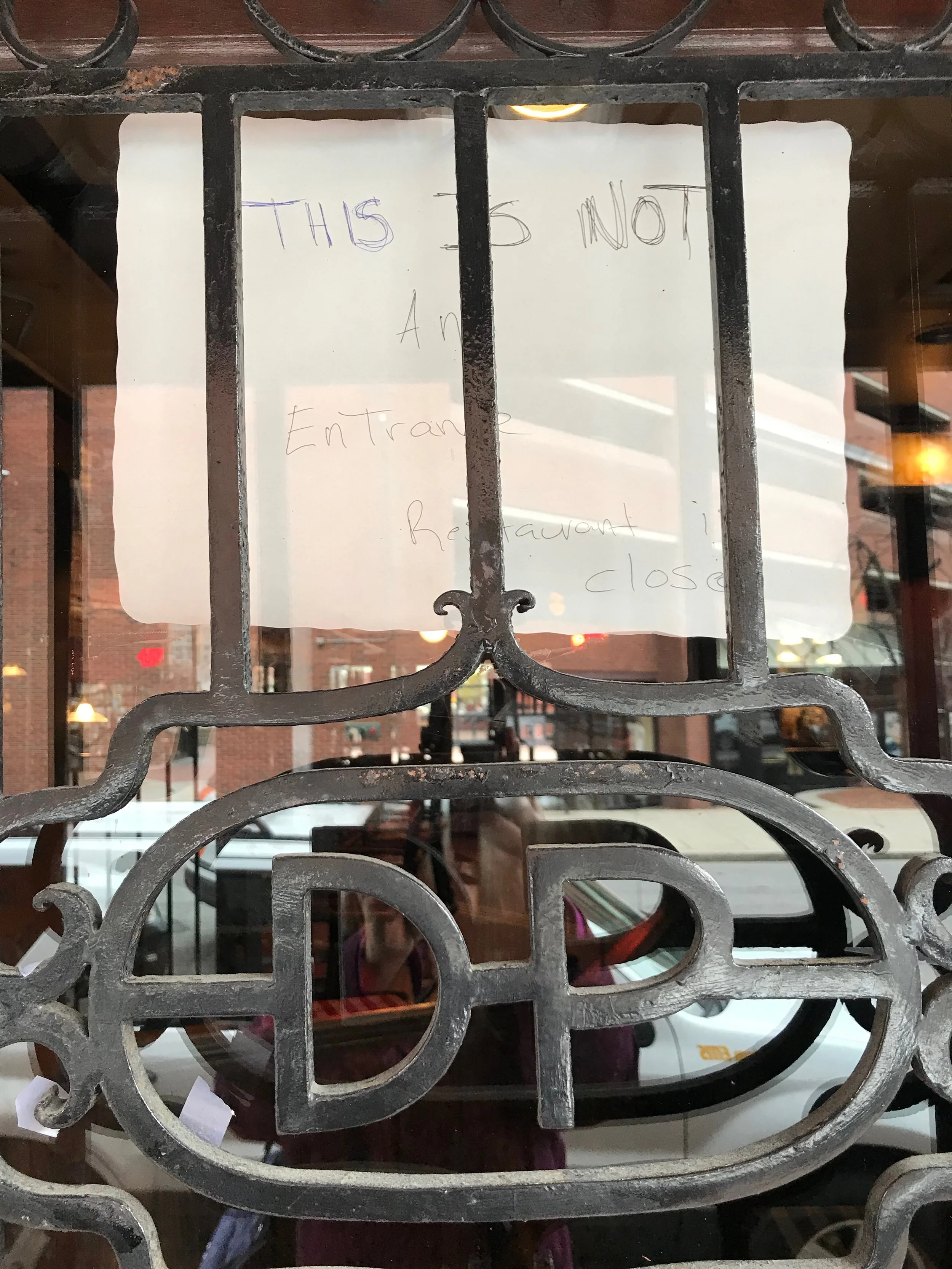

A handwritten note scrawled on the back of a paper placemat and taped to the the Clinton Street entrance door, behind the restaurant’s black, wrought iron D-P door grate. Photo: Karen Bento

Patricia Reyes, general manager, walks around making sure staff know what paperwork needs to be filled out. Felix Hernandez, a manager who has been part of Durgin-Park for decades, helps empty overstuffed trash cans. Like any big family, everyone chips in so that when the lights are turned off for good, everything will be in its place.

A few lines from “Just a Boy,” a poem that has been printed on the back of the menus since the 1940s, jump off the page:

Could he know and understand,

He would need no guiding hand;

But he’s young and hasn’t learned

How life’s corners must be turned.

Its sentiment still rings true today. Who knows what will appear right around the corner? Maybe an answer to everyone’s prayers. Perhaps someone to breathe new life into Durgin-Park again.

Saturday, Jan. 12, 2019 marked the last night patrons could sidle up to the bar at the Gas Light Pub and order John Durgin Ale (est. 1826) on tap. An empty, ceramic beanpot hides amid stemmed lager glasses and bottles of liquor left over from the restaurant’s last night of revelry. Photo: Karen Bento